Didem Fırtına

His exalted name, “Light,” touches the darkness

and everywhere is filled with light.

The letters written from a brilliant world

are revealed to the hearts;

Then the Divine command,

“Read in the name of your Lord!”

descends and becomes our intentions.

We look around the Earth and believe that we start to sail into the dark upon reaching the depths of the skies, the land, and the oceans. But if we look with care, we may notice that the inhabitants of those places often inform us of the beauties they are created with.

The depths of the oceans, especially, are where what we see leave us amazed. From microscopic bacteria to giant squids, and from tiny lighted jellyfish to spiny skin, many creatures, from ascidians to some sharks and stingrays, turn on their lights, literally, illuminating the darkness of the deep sea. This biological light-producing process in the body of some animals is called bioluminescence. It is astounding that these creatures can emit biological light with no change in their body temperature. Normally, light is formed by emitting heat. This basic principle applies to some of the most common sources of light that we know of, such as campfires and electrical lightbulbs.

A mechanism that produces light without heat has been created in some insects living under the sea as well as those on land. The basis of biological light production is generally the oxidation of luciferin, i.e. its conversion to oxyluciferin. The enzyme necessary for this chemical reaction to occur is luciferase.

Most living creatures that can produce bioluminescence live in deep, dark areas of the world’s various seas and oceans. Some of the inhabitants of these depths emit strong blue (secondarily green) light at an average wavelength of 475 nm. An interesting note is that underwater life forms are often created with sensitivity to the wavelengths of blue-green lights mentioned above. In rare cases, there are also sea creatures that emit light in the yellow-red wavelength range.

Animals with the ability to emit light are also usually given excellent control mechanisms so that they can use their equipment as a weapon. They can turn their lights on and off in a flash and can utilize complex chemical and neurological mechanisms that provide functions such as adjusting the intensity, color, and direction of the light. Creatures that produce light underwater sometimes do not need to use the light in order to see where they are going. Instead, they tend to use these marvelous gifts in a variety of strategic ways. Some will try to attract the attention of their prey; others will attempt to ward off predators and aggressors; still others will use their lights to indicate that they are ready for reproduction. It is even possible for some creatures to utilize several of these functions at the same time.

Let us now examine some specific species and how they employ bioluminescence.

Light vomiting shrimp

One of the most interesting examples of bioluminescence in animals is the light-emitting deep-sea shrimp Acanthephyra purpurea. This shrimp will actually vomit light from its mouth as a last-ditch effort to deter predators. The intent is to disorient, confuse, and even temporarily blind other creatures, similar to the effect of a flashbang grenade, so that the shrimp can retreat into the dark. As a result of their research on the shrimps, marine biologist Edith Widder states that the chemical substances sprayed are not blue when they are in the body and that the blue light production occurs when the luciferin substance in the sprayed liquid comes into contact with the oxygen in water.

Loosejaw fish

There are at least 42 recorded families of bony fish that have bioluminescent properties. One of them is the Photostomias guernei, or the “loosejaw fish”. This fish has a remarkable organ that emits light on the sides of its eyes. These lights, which resemble the headlight lamps of our cars, are not constantly lit, in order to avoid waste. When hunting, the fish illuminates the way ahead with the light it produces, and it can turn these lights off when they are no longer needed. A wonderful feature of this organ is that, just like headlights, a highly reflective layer is created behind the main center of the light. The reason that the fish is able to turn the light off may be because its black velvety body is contrasted by the light color of the organ and would thus attract much unwanted attention.

Deep sea hatchetfish

Bioluminescent systems were also given to creatures in order to act as a means of camouflage. They work phenomenally for both hunting and survival in situations where blending in with the environment is paramount for catching prey or evading predators. In the depths of the underwater world, the silhouette of an animal bathing in light is an easily recognizable target. One of the best examples of this phenomenon is the deep-sea hatchetfish. The fish has been created with its eyes on top of its body and its mouth facing upwards, making it easier to hunt. It also emits bioluminescence from its abdomen to provide camouflage against more aggressive, larger fish that swim lower than itself. The color of the light emitted makes it difficult to recognize the fish from below as it perfectly matches the color intensity of the environment. In the meantime, if the sunlight that hits the sea is interrupted in any way, the fish will turn off its lights and the camouflage will continue.

Black dragonfish

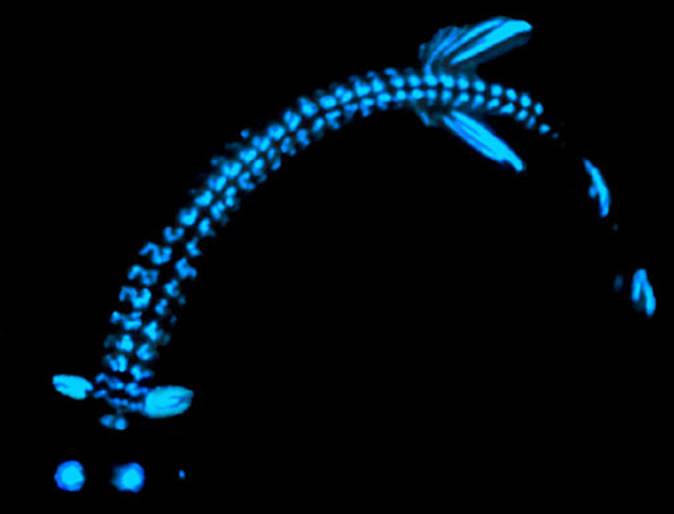

Diversity in the light organs of the scaleless black dragonfish (Melanostomias bartonbeani)

This species of black dragonfish (Melanostomias bartonbeani) takes advantage of luminescence in a number of ways. An illuminated area next to the eyes is used to find prey and send signals to its mates. The black dragonfish’s chin also has an illuminated extension that dangles in the waves as bait for naive prey. In addition, a set of small organs of light arranged along its abdomen play a role in concealing its silhouette. Furthermore, light-emitting pocket-like structures surrounded by a gelatinous capsule embedded in the skin are used as alarm systems. The bioluminescent systems within this creature are immensely complex and beautiful, and when observed in detail reveal the dazzling splendor of the world that we live in.

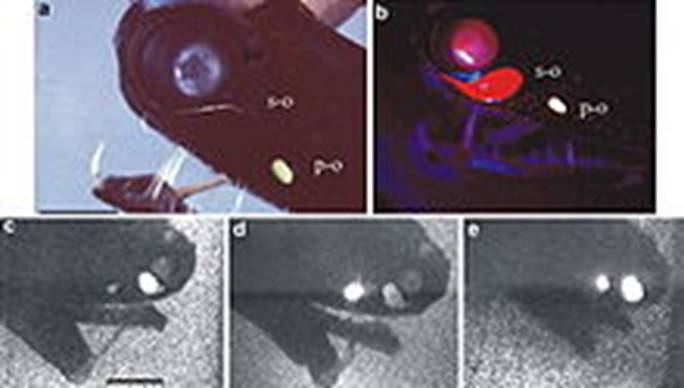

Fish with 3 different types of illumination

The Northern Stoplight Loosejaw (Malacosteus niger) has three different types of light organs, the complex use of which cannot be possible without top engineering skills. The wide, drop-shaped, illuminated organ under its eyes emits a red light at a wavelength of 702 nm as if it knows the laws of optics under the sea. This red light is not visible to most deep-sea creatures, for it is quickly absorbed in water. Yet, with this red light this fish is able to have vision in a close proximity while remaining largely undetected. This is similar to infrared binoculars soldiers use for night vision without giving away their position. The loosejaw is thus a dangerous hunter that has an edge over its prey. There also exists a blue light-emitting oval section, behind the organ, that emits red light and is usually larger in males. A third light organ is round and smaller and is located between the eyes and the red-light organ.

Angler fish

The angler fish is one of the most iconic fish of the deep ocean due to its famous rod and bioluminescence. The angler fish does not actually produce its light on its own: the light is credited to bioluminescent symbiotic bacteria that inhabit the end of the rod on their forehead. This illuminated part, which resembles a worm-like bait, is very attractive to small fish. These fish are thus lured to the angler expecting a quick snack, but instead the angler swallows them whole with its massive mouth. While doing their task of helping the angler hunt small fish, the bacteria maintain a symbiotic relationship with the fish and also find an environment in which to proliferate. In this way, they form a good example of cooperation and solidarity. One may wonder: how can such a mutual agreement come into fruition between a fish and some bacteria which are deprived of a nervous system, mind, and consciousness?

One of the reasons that marine biologists are interested in light-emitting bacteria is the wide-lit regions called the “Milky Seas.” These can be observed in satellite images of Earth. Recently, satellites helped detect a bioluminescent area of roughly 5,946 sq. mi in the Indian Ocean; scientists wondered if some bioluminescent bacteria or Dinoflagellate-type flame-colored algae may be the cause of the phenomenon.

Alarming jellyfish

The luminescence of some marine life serves as an alarm or distress siren. A remarkable example of this is the Atolla jellyfish (Atolla wyvillei), an elegant inhabitant of deep waters. This jellyfish produces blue lights that are spread in circles in the water when it is attacked. Thanks to these lights, it tries to draw the attention of larger and stronger animals than the initial attacker in order to escape from harm’s way.

As can be observed in some species that we are familiar with, such as fireflies, the bioluminescence feature that is full of wisdom granted to some living beings is a thought-provoking biological miracle which does not only make us ponder where they got these abilities from but also reveals how so many intricate patterns are found in nature.

References

- Steven H.D. Haddock, Mark A. Moline and James F. Case. 2010. Bioluminescence in the Sea, Article in Annual Review of Marine Science, DOI:10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081028 Source: PubMed.

- Edith A. Widder. 2001. Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution, Fort Pierce, Florida, Marine Bioluminescence, Bioscience Explained, vol 1, no 1, pp. 1-9.

- Edith A. Widder. 2010. “Bioluminescence in the Ocean: Origins of Biological, Chemical, and Ecological Diversity,” Science, vol. 328, pp. 704-708.

- www.wired.com/2012/01/glow-little-spewing-shrimp-glow/ March 28, 2018.

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malacosteus_niger / April 1, 2018.

- Harold, A. 2015. Malacosteus niger. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T190149A21909439. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T190149A21909439.en.

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/190149/21909439